The ILWU Story

The ILWU Story

Organization in Hawaii

The ILWU's principles of rank and file unionism have never been more severely tested or more magnificently successful, than in Hawaii-where over half the U.S. membership of the ILWU lives and works.

The union's victories were achieved after 100 years of bitter experience and sacrifice by Hawaii's workers, successfully resisting terrible repression by many of Hawaii's most powerful employers and government officials.

Five big landholding companies controlled the economy of the Territory of Hawaii. Their interlocking directorates and close cooperation allowed them to act as one great combine that dominated the Territorial government and every aspect of the Islands' political, economic, an cultural life.

When the Big Five took over the bulk of the arable land of the islands in the early 1800s, they destroyed the traditional economy and set up a plantation system that forced most workers to live in company housing and work the plantations for miserable wages, under brutal working conditions.

The employers dealt severely with protesters and smashed every attempt workers made to improve their conditions. They encouraged racial divisions and suspicion to the point that when the workers sought to organize into unions, they made the tragic mistake of following racial lines. Hawaii today has a richer mix of races and nationalities than any other area its size, largely due to the companies' lust for cheap labor.

Japanese, Chinese, Filipino and Portuguese workers were imported or lured to the Islands in waves; as one group got established and began to demand its rights, the next one was brought on. When they organized during these early years, workers in the same industry or plantation formed racially and ethnically segregated unions, without any coordination or communication. These divisions weakened the workers during confrontations with the employers.

When, for

example, Japanese and Filipino plantation workers struck separately on the

island of Oahu in

1920, the employers were able to drive them from their company-owned homes.

In 1924 and again in 1935 the Filipinos organized and struck again along racial lines, and with similar results: they and their families were evicted from their homes and left to fend for themselves on Wailokou Beach. Their leaders were jailed. The Japanese continued to work.

Also, in 1935, the Hilo longshoremen, chartered by the old Pacific Coast District of the ILA and inspired by the achievements of the mainland longshoremen in 1934, struck to force the reinstatement of a group of discharged workers.

They won the battle and survived as a union-although they lacked satisfactory collective bargaining agreements, and were still outside the majority of Hawaii's workers, who were employed on sugar and pineapple plantations.

When longshoremen and island boatmen went on strike again in 1938, police attacked their picket lines, injuring some 50 strikers during what is remembered today as the Hilo Massacre. The strike was broken, and the latest resistance to Big Five exploitation apparently stamped out.

These experiences demonstrated that racial unity was necessary for unions to succeed on the Islands-and that the unions needed to be tied to the mainland West Coast waterfront on the one end, and integrated into the whole economy of Hawaii on the other.

And

any successful union would have to be Territory-wide,

covering all companies, all plantations, and all ports, paralleling the

structure of the Big Five.

And

any successful union would have to be Territory-wide,

covering all companies, all plantations, and all ports, paralleling the

structure of the Big Five.

The answer was to organize all workers in all facets of the Islands' basic industries, including sugar and pineapple growing and processing, which was accomplished by the end of 1945 after the arbitrary restrictions on union organizers imposed by U.S. military forces and court injunctions during the early years of World War 11 were lifted.

Striking sugar workers in 1946 employed these lessons and achieved one of the biggest victories in ILWU history.

The victory consolidated the ILWU in Hawaii: only union sugar would be moved from the plantations through the mills, over ILWU docks in the Islands and on the West Coast, and through ILWU-organized refineries on the mainland. And the militant, democratic traditions of the union helped end, once and for all, the employers' formerly successful division of the workers along lines of race, color, skill and even marital status.

Then, in the summer of 1947, the unionized pineapple workers were locked out. The Islands were swamped with hysterical redbaiting and anti-union propaganda against the ILWU. Employers provoked revolts within the union, trying every possible device to split and weaken the membership. They planted unsubstantiated charges of ILWU corruption and Communist domination.

They tried to promote other unions, and to revive racial and ethnic divisions between the workers. In response the ILWU called an Islands-wide convention to discuss and debate the issues in January 1948. In a subsequent referendum the membership voted by more than 98 percent to stick with the union.

Through 1948 and early 1949, the employers pushed wage cuts, forced a 68-day lockout on the workers at the Olaa plantation, and kept up a relentless search for weak points in the union structure, trying to find local union leaders who might not have the fortitude to endure a protracted struggle, or who might have personal ambitions or conflicts with other leaders and members that could be manipulated to divide the union's ranks.

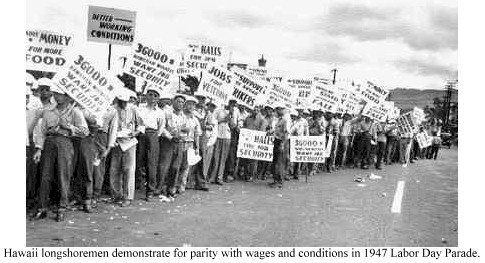

By 1949 the Big Five felt ready for a showdown. They provoked a strike by holding out against the Hawaii longshoremen's demand for wage parity with their mainland counterparts.

Longshoremen in Hawaii did the same work on the same cargoes on the same ships for the same companies, and belonged to the same union as longshoremen in West Coast ports.

Yet under the Big Five's "colonial wage theory," they had always been paid substantially lower wages and worked under inferior conditions. Hawaii longshoremen struck May 1, 1949 over equal pay for equal work - and fought on to preserve the unionism that the 1946 sugar strike had established in the Islands.

The 157-day strike tested every segment of the union's organization in Hawaii. The ILWU membership fought and prevailed against enormous odds: the power and wealth of the Big Five; the employers' refusal to go to arbitration; official government scab-herding and strike-breaking; innumerable arrests and court actions; and even opposition from within the labor movement.

Members of both AFL and CIO maritime unions scabbed. CIO officials refused assistance or sabotaged the strike outright, caught up in the CIO's national campaign to expel militant and progressive unions like the ILWU from their ranks if they did not jump on the anti-Communist bandwagon of the Cold War.

The ILWU's eventual victory gave the Hawaii longshoremen the same kind of recognition and status won by the mainland longshoremen in 1934. It brought their wages up to mainland standards, putting the colonial wage theory to rest.

Another major achievement in the union's mobilization to win the strike was the amendment to the mainland's West Coast longshore agreement providing that West Coast longshoremen would not have to work cargo to or from a U.S. "port where there was a bona fide strike."

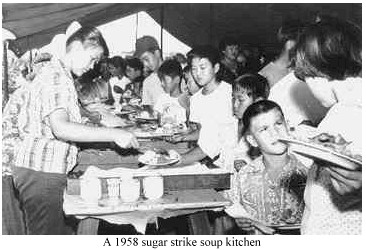

After the '49 strike the union moved steadily to get a shorter work week and other contract improvements for sugar and pineapple workers. Increasingly, the efforts of the union were aimed at socia gains built upon the solid foundation of a growing union organization. Employers met the union's advances with an attempt to break down industry-wide bargaining, starting with pineapple because it appeared to be the weakest section of the ILWU.

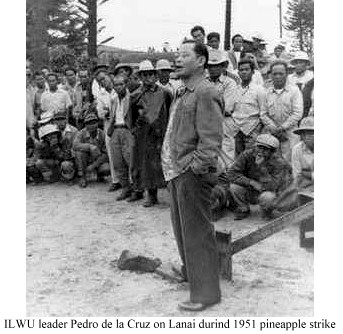

All the other groups in the pineapple industry accepted a minimal wage offer in 1951. But the pineapple workers of Lanai hung tough in a seven-month strike. They won, with the entire union supporting them. And they returned to work with a settlement which exceeded their original strike demands and benefited pineapple workers> throughout the islands.

Union members in Hawaii learned the lesson that only the full strength of the ILWU could guarantee industry-wide bargaining. As a result, the separate local unions in Hawaii further consolidated to increase the ILWU's fighting strength and to bring it to bear whenever necessary.

Today all ILWU workers in Hawaii-longshoremen, sugar workers, pineapple workers, hotel and tourist industry workers, and workers in other industries - are in one big union, Local 142 of the ILWU, except for security personnel organized into Local 160.

Meanwhile,

the union in Hawaii continued to grow and fight throughout the 1950s. In

sugar, the ILWU

established an industry-wide medical program, sick leave, and paid vacations

and holidays - all unique in

the agriculture industry. After the union's intensive mobilization and

strike vote in 1954, the ILWU won

the first pension plan ever negotiated for agricultural workers in

the United States.

Meanwhile,

the union in Hawaii continued to grow and fight throughout the 1950s. In

sugar, the ILWU

established an industry-wide medical program, sick leave, and paid vacations

and holidays - all unique in

the agriculture industry. After the union's intensive mobilization and

strike vote in 1954, the ILWU won

the first pension plan ever negotiated for agricultural workers in

the United States.

And, culminating a drive for shorter hours in sugar and pineapple that had been going on since 1950, the 40-hour week, Monday through Friday, was established for the first time ever in agriculture./font>

Union contract protection against discrimination for reasons of race, creed, color or politics, brought political freedom. Before that, politicians not favored by the management could not hold rallies in plantation camps, and workers were afraid to attend the rallies held on public roads.

In many places, workers felt they were not even secure inside the voting booth. The new freedom for union workers made it possible for opposition parties to grow and for opposition opinion to be heard, and opened up real freedom of political choice to voters outside the union.

Fifty years of unbroken one-party control of the territorial legislature ended in 1946. Independent political action by the ILWU re-wrote Hawaii's labor laws for the benefit of working people.

The

gains in Hawaii did not come easily. The employers and the government

stepped up their anti-union activities under the guise of anti-Communism.

When intimidation failed, they turned to outright frame-ups, as in the case

of Jack W. Hall, ILWU's regional director in Hawaii.

The

gains in Hawaii did not come easily. The employers and the government

stepped up their anti-union activities under the guise of anti-Communism.

When intimidation failed, they turned to outright frame-ups, as in the case

of Jack W. Hall, ILWU's regional director in Hawaii.

FBI agents seized Hall at his home at 6 a.m., August 28, 1951. He was indicted along with six other people, who, though not connected with ILWU, were named as Communists. They were charged with conspiracy to violate the federal Smith Act by advocating the overthrow of the government by force and violence.

Federal agents tried to get Hall to make a deal: if he would lead a revolt to take the Hawaii membership out of the International Union, they would arrange to have his indictment suppressed.

He refused, and was convicted along with the other defendants after a trial that always focused on their political beliefs-not on their actions. Union members greeted the June 1953 "guilty" verdict with an all-Islands walkout.

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals reversed his verdict in 1958, in time for Hall to help the ILWU close out its successful campaign for statehood for Hawaii-and to celebrate a victorious sugar strike which for the first time saw the employers indicate their acceptance of the ILWU as the chosen representative of the Islands' sugar workers.

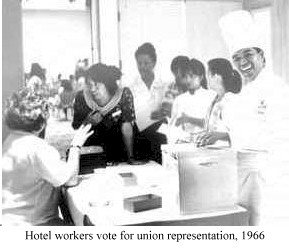

By 1967, just as the last non-union waterfront firm was organized and all Hawaii's longshoremen and clerks were brought into the ILWU, members of Local 142 witnessed the rapid rise of another industry built on the backs of a low-wage work force: tourism.

The new industry provided many opportunities for new organizing, but over the next 20 years, as it attracted a larger and larger share of corporate investment, it also threatened to displace other industries, including sugar and pineapple, as the mainstays of the island economy.

The

union responded on many levels. It increased organizing activities among

unorganized workers, and began training programs to provide unemployed and

underemployed displaced workers with the skills needed by the hotel and

related tourist industries.

The

union responded on many levels. It increased organizing activities among

unorganized workers, and began training programs to provide unemployed and

underemployed displaced workers with the skills needed by the hotel and

related tourist industries.

Workers in many trades responded to the union's message of unity, militancy, and democracy-and often showed their appreciation for ILWU-sponsored job training by signing up with the union after they were employed.

In keeping with the lessons learned in the 1940s, Local 142 has kept on educating new and veteran members alike about unionism and social issues. It held its first Labor Institute on collective bargaining, grievance handling, labor law and history, organizing, political action, and union administration in 1987.

Now a regular project, the Institute recruits instructors from all over the country (and the ILWU) who join Local 142 members in an intensive, week-long retreat that provides challenging and rewarding experiences for all involved. Costs of the Institute are paid by Local 142 and its units, with a major subsidy from the International Union.

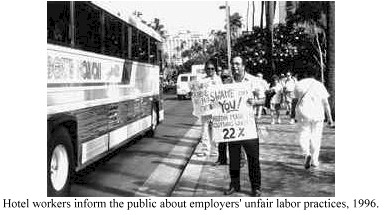

These constant efforts to

organize, educate, and mobilize its membership have helped Local 142 endure

everything from natural disasters to bitterly anti-union employ ers. In 1996

and 1997 ILWU members in the hotel industry were, as one local officer

described it, making "progress while locked in trench warfare.

ers. In 1996

and 1997 ILWU members in the hotel industry were, as one local officer

described it, making "progress while locked in trench warfare.

"The confrontation began in 1995 when hotels refused to provide a "snap-back" on wages (the resumption of a 7 percent wage increase deferred by union members to help the stressed tourism industry).

Instead, employers proposed new takeaways in benefits and overtime pay, and elimination of the dues check-off system. Once again the Local 142 response centered on education, member action short of strikes, pressure on a hotel's sales and public image, pointing out the employer's unfair labor practices, and other pressure points.

By early 1997 the major hotels were breaking ranks one by, one and reaching accommodations with the union.

At the same time, the rank and file was pulling together to grapple with the general economic crisis caused by the decline of the sugar and pineapple industries combined with a major downturn in tourism—drawing heavily on the membership's heritage of unity and innovation that helped bring justice and democracy to Hawaii only 50 years ago.