The ILWU Story

The ILWU Story

The Marine Division

The independent Inlandboatmen’s Union of the Pacific (IBU) affiliated with the ILWU in 1980, forming the union’s Marine Division. Made up primarily of workers aboard tugs, barges, tour boats, and passenger ferries, the IBU has represented workers from San Diego to Alaska, and across the Pacific as for as Guam and Hawaii.

The

current organization began as the independent Ferryboatmen’s Union in

California more than 70 years ago. In the early 1920’s it became the first

San Francisco Bay Area union to admit members of all races.

The

current organization began as the independent Ferryboatmen’s Union in

California more than 70 years ago. In the early 1920’s it became the first

San Francisco Bay Area union to admit members of all races.

In keeping with this progressive tradition, the IBU in 1937 became the first West Coast affiliate of the CIO, beating the ILWU into the fold by a few months.

A decade later the IBU became an affiliate of the Seafarers’ International Union (SIU), a partnership that would not endure past the 1970s as the SIU repeatedly infringed on IBU autonomy and undercut its traditional occupational and geographical jurisdictions.

The IBU voted overwhelmingly to disaffiliate, but harsh economic and political realities compelled the union to form a new alliance.

In 1980 it joined the ILWU which, in keeping with its own traditions of democracy and local autonomy, guaranteed the IBU it would retain all its traditional jurisdictions, including those obtained through new organizing efforts. The affiliation agreement also provided that IBU members could fully participate in the ILWU’s International election as both candidates and voters.

Further,

the ILWU’s International resources would be made available to the IBU as

requested for research, political action, organizing, and occupational

health and safety.

Further,

the ILWU’s International resources would be made available to the IBU as

requested for research, political action, organizing, and occupational

health and safety.

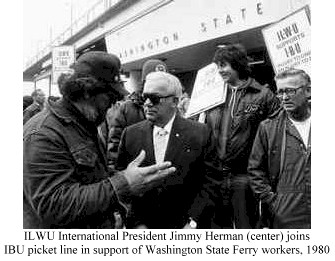

The affiliation agreement of 1980 was in part triggered by the pivotal role played by the ILWU’s Puget Sound longshore locals in support of a strike in 1980 by 700 IBU members employed by the Washington State Ferry System.

When the state court jailed the strike leaders, the ILWU shut down the Puget Sound ports for 24 hours on April 15th, 1980. The stoppage produced serious bargaining, a clear-cut IBU victory, and concrete evidence of how well the two memberships could work together.

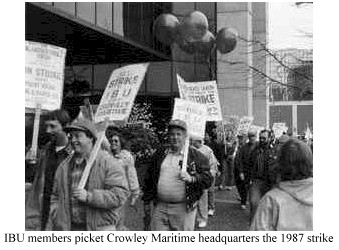

A few years later, this unity and mutual respect helped the IBU to establish jurisdiction and union standards aboard the previously non-union barges or JORE Stevedoring in 1986, and to preserve its jurisdiction after a bitter and protracted strike against Crowley Maritime in 1987.

After 1987 the IBU showed renewed vigor. It pioneered new organizing drives and took an active role in the political action programs of the ILWU district councils. While maintaining the best maritime working conditions in the world, it also benefited from the infusion of new members and traditions from ILWU Local 37.

Like

the IBU, Local 37 first came into the ILWU after having been affiliated with

another union. Local 37 traces its roots to organizing efforts among

seasonal cannery workers initiated by Filipino veterans of the Hawaii sugar

strike of 1924.

Like

the IBU, Local 37 first came into the ILWU after having been affiliated with

another union. Local 37 traces its roots to organizing efforts among

seasonal cannery workers initiated by Filipino veterans of the Hawaii sugar

strike of 1924.

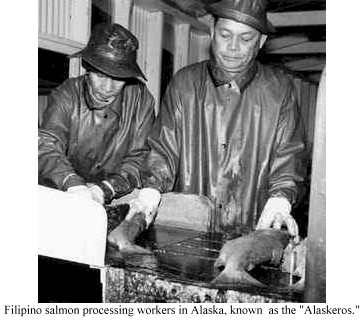

By 1933, these workers now in the salmon processing industry of Alaska and known as the "Alaskeros," were chartered by the Cannery Workers and Farm Laborers Union.

The leaders of this organization recognized that for the seafood processing workers’ local to be successful it had to be a full-time operation, and its approach to organizing and representation had to be multi-racial.

Their efforts received a major boost from striking West Coast maritime union in 1936-37. But a split developed between the more militant and progressive members, who supported multi-racial unionism, and those who favored the AFL’s racially divided locals.

The progressives went with the new CIO as Local 7 of the United Cannery, Agricultural, Packinghouse and Allied Workers of America (USAPAWA).

Local

7 grew rapidly to more than 7,000 members by 1938. Some setbacks were

suffered defending against AFL raids, but the local regrouped and grew

during World War II. Post-war anti-labor attacks, a changing workforce, and

internal factionalism led to another decline.

Local

7 grew rapidly to more than 7,000 members by 1938. Some setbacks were

suffered defending against AFL raids, but the local regrouped and grew

during World War II. Post-war anti-labor attacks, a changing workforce, and

internal factionalism led to another decline.

By 1947 the union couldn’t afford to pay per capita due to UCAPAWA (which by then had become part of the FTA – the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America).

Foremen and supervisors were allowed to become members of the union. The presence of these managerial employees gave employers the opportunity to influence the union’s affairs and decisions, further weakening the organization’s effectiveness.

The militant and progressive embers regrouped at this low point and stepped forward as a new rank and file committee.

Support for their efforts came

quickly from the ILWU, the Marine Cooks & Stewards, and the

fishermen’s union. Then the redbaiting and political persecutions of the

McCarthy era hit. The FTA was ex pelled from the CIO for alleged

"Communist domination," and government actions to deport immigrant

union activists decimated the new leadership.

pelled from the CIO for alleged

"Communist domination," and government actions to deport immigrant

union activists decimated the new leadership.

In this weakened and increasingly isolated state, the membership of Local 7 allied with the ILWU, and was chartered as ILWU Local 37 on March 26th, 1950.

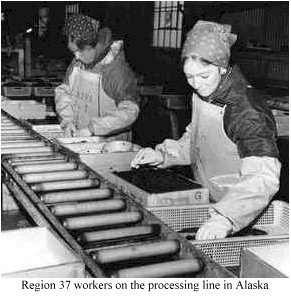

As of 1980, Local 37 was the only union to win travel pay for seasonal workers in Alaska. Between 1983-1985, the union’s industry master contract was broken, but contracts with two employers with 10 locations still set the standard for wages and conditions.

The composition of the union’s membership has changed drastically: with a decline in the number of Filipino processing workers, there has been an increase in the number of white college students and Hispanic workers – but Filipinos are still the majority of the local’s members.

Organizing a seasonal industry with a transitory work force – many of whom work offshore aboard factory ships – is particularly difficult.

Being so distant from other ILWU locals and the union’s power base made it a hard local to service and a struggle to just maintain a union presence in an industry that is 90 percent non-union.

As the IBU’s historic jurisdiction included certain shoreside facilities in Alaska, Local 37 affiliated with the IBU in 1987 and became Region 37, where it has consistently been a progressive force and continues to represent non-resident Alaskan seafood processing workers.