Seattle Waterfront History

Seattle Waterfront History

The First Hundred Years Are The Hardest

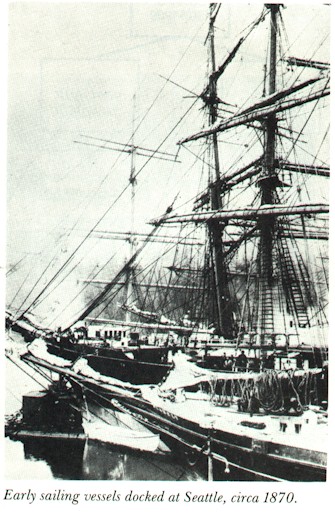

The life of a Seattle along-

the- shore man in the 'good old days' of the early 1880's was not a

piece of cake. You piled out of the sack long before dawn because the

hours of work were "from can't-see to can't-see" and no matter

what the weather you did not reach for a light switch nor turn up the thermostat nor head for

the bathroom.

reach for a light switch nor turn up the thermostat nor head for

the bathroom.

You fumbled in the dark for your boots and stumbled out the back door and headed for the old outhouse. If you wanted to wash up in hot water you built a fire and heated some --- provided you remembered to pack in firewood and a bucket of water from the pump out back.

You knew a ship was hiring that morning not from a shipping news supplied radio, telegraph or telephone but because you saw her come in and drop her sails last night just before dark. Did you jump in the car or grab a bus? You walked, buddy --- and no paved streets or sidewalks --- unless you had a horse.

Union hall? Peg Board? Science fiction! you had to face the Man at the shape-up and if you had fallen from grace with the bostrodonkovitch, you'd get, if you got any job at all, the worst work available. Handhauled cargo? Oh, yes, indeed. Every piece of cargo that was discharged from or loaded aboard the ship was fingerprinted many times.

Or bore stray hairs and perfume from the horses that sometimes hauled it to the ship. The Iron Law of Wages, as an old British writer called it, was in full effect. Employers paid the lowest wages they could, based on what the most hungry and desperate would accept. Nothing personal, you understand, "business is business.'' Making a living as a longshoreman was out of the question.

It was an on again off again

casual labor proposition.  The

situation began to change with the California Gold Rush of 1848. things

boomed down there and suddenly Puget Sound ports were In a remarkable

position.

The

situation began to change with the California Gold Rush of 1848. things

boomed down there and suddenly Puget Sound ports were In a remarkable

position.

Those dense stands of huge timber that crowded the shoreline sprouted dollar signs. California investors headed north to build sawmills and cash in on the bonanza.

You could sell lumber to California as fast as you could cut it and ship it. The Great. Northern Railroad began building Northwest. Coal was found around Mt. Rainier and mines began to produce. The fish packing industry began to grow.

Shipping flourished, not just coastwise but foreign trade as well. Longshore work began to look like more of a steady occupation.

There were problems. When winter chased the loggers and miners out of the woods and hills they came to Seattle. A summer's wage did not last long.

And a man has got to eat. So they, and the harvest. hands from east. of the mountains, competed for any work available. At any price. A thick head and a strong back could do most any Longshore work at that time.

But when it came to loading out a ship certain skills and experience were necessary to make a tight stow, quickly, to get all possible cargo aboard and to prevent damage or shifting, endangering the ship. So probably a nucleus of savvy and able men worked when work was available.

The bulk of the men had to fight the competition. "Enjoy' the chicken today, kids, tomorrow well be eating feathers." The Man and his lieutenants who ran the shape-ups got fat on pay-offs. Another cute trick --- when a ship hit home port a complement of longshoremen was hired.

These men stayed with the ship, eating and sleeping aboard, working the cargo for all the days or weeks she moved around the Sound. Thirty cents an hour And got paid only for actual time you worked cargo.

life aboard a Sailing ship was tough enough for the crew at sea. Pile a small army of longshoremen on board, sleeping all over the place, no toilet nor bathing facilities --- well, probably you did not have to see the ship to know it was coming. With a little breeze blowing inshore you could smell it. Naturally, such working conditions did not draw men from the upper rungs of the social / economic ladder.

They may have fit the old ditty: "Rough and tough and full of fleas and never been curried above the knees'' but they were not stupid. They knew about trade unions and they knew they needed one.

Stories of the struggles of trade unions in the East were carried to them by seamen --- water was the only form of communication to Seattle in those days --- and they knew to build an effective union directed to longshoremen's interest meant facing awesome and deadly opposition. After all, organizing for better wages arid conditions threatened the Iron law of Wages and by God that smacked of ''foreign agitators" was un-American.

For generations employers had known they were masters of the government and the police and some even believed they were direct allies of God As George F. Baer, a plutocrat, summed up the employers' view of labor relations: 'The interests of the laboring man will be protected and cared for not by labor agitators but by the Christian men to whom God in His infinite wisdom has given the control of the property interests of this country."

The longshoremen knew Robber Barons and Industrial Tycoons were using armed police and United States Army troops to ruthlessly and violently break strikes and smash unions, slaughtering strikers on the streets In places as close to Seattle as San Francisco.

But when a man gets hungry enough that his belly button rubs against his back bone it generates a spark that leaps to his brain and he realizes he has no other way to go but to organize. The Coast Seamens Union and the Knights of Labor, while lacking punching power were at least on the scene around Puget Sound.

The longshoremen wanted something better. The first longshoremen's Union north of San Francisco was the Stevedores, Longshoremen and Riggers Union organized in Portland, 1878.

In March of 1886 Tacoma longshoremen followed suit and on June 12, 1886 Seattle longshoremen in the shack of a an named Terry King and formed the granddaddy of the ILWU Local #19, The Stevedores Longshoremen and Riggers Union of Seattle Ind.,. Washington Territory.

(It. is a shame, and a tragedy, that we cannot name those Brothers who organized that Union, because somewhere along the line all the old union records got deep sixed.) The Union hereinafter referred to as "Our Guys" did nor waste time.

They got preferential hiring, still had tile shape-up but The Man had to choose Union members first. Which, no doubt, made him most unhappy. Our Guys got a wage Increase but went on the War path to stop the hated practice off riding a crew of longshoremen from port to port. This took them three years.

Life was improved, of course, for Our Guys but the light was not over and they had built a time bomb into their organization. It was part trade union and part cooperative. The original members became shareholders. They did some of their own stevedoring contracting.

Shareholders got preference of employment, sort of a closed shop within a closed shop. Bad news. In 1894 Our Guys struck the major employer, Pacific Coast Steamship Company, to prevent a wage cut, and they took a dumping. Non-shareholding members, who were angry at being made second class citizens in their own union, took a hike and left. the shareholders holding the bag. So there were Our Guys, up that famous creek without a union. Down, but not out.

Tacoma's union suffered the same fate for same reason. The labor movement. everywhere was in a state of evolution, unions opened and closed like jack knives, reorganized, split, merged, got Smashed, sold out, learning and trying. The Wobbles blew in and out like a typhoon, leaving their mark.

Our Guys in 1900 formed the Seattle Longshoremen mutual Benefit Association which affiliated with the ILA-AFL and became Local 163 with 300 members, that only lasted for two or three years: then for awhile. 1904 to 1907, Our Guys split. an had two Unions, Local 552 of the ILA and Local I of the Pacific Coast Federation of Longshoremen of the Pacific. They merged again in 1907 under the banner of the Longshoremen's Union of the Pacific which lasted two years.

In 1909 Our Guys were back In the ILA, local 38-12. Right from the beginning the employers had formed coastwide alliances to combat unionism.

They had much better Unity than did the longshoremen. Under the name of the Waterfront Employers Union they played not only men in one port against another port (you don't like it well take it to Tacoma) but gang against gang (that. gang up forward is making you guys look like bums) and even member against member on the basis of religion, race and just. human traits such as jealousy.

It took a lot of lost strikes and broken Unions and the loss of many working conditions before longshoremen finally wised up to the fact hat the Employers knew more about Strength Through unity than they did. In 1912 the Waterfront Employers, after a long strike, drove Our Guy's union off the clocks of Seattle.

Wages and conditions went down the tube. Men were working as long as 72 hours at stretch to finish a ship. Corruption of the hiring procedures hit a new low.

Our Guys hung onto their union although it was practically helpless. In 1919, in fact, Local 38-12 voted to take part in the Seattle General Strike, called by the AFL Central labor Council, and were a part of 68,000 union workers who brought Seattle to a stand still for five days. In October of that same year, the AFL Central Labor Council condemned the shipment of rifles being sent to the White Russian Army. Local 38-12 defied "up-town" opinion by refusing to load them.

In the depression that followed the end of World War I, Our Guys asked the employers to hire men in rotation to equalize earnings give everyone a share. The employers refused flatly and Local 38-12 hit the bricks. They were totally defeated.

Even the ILA gave them a kicking by pulling their charter because they had called a "wild cat strike" this began 13 years of practically no union action on the waterfront of Seattle. Again, Our Guys were down. But not out then came the time of the Blue Book Union. Foisies Fink Halls. On paper the plan sounded good.

From the start the employers made it clear no union was to be involved. A committee of longshoremen and employers was set lip to screen time longshoremen. Steady employees of the port were registered first as regulars.

Transient or casuals were screened and men who lived in Seattle became regular casuals. There was a central hiring hall. Registered men were safe from outside competition for the work.

But. Employers still did the hiring. Still a form of the shape-up Our Guys faced speed-up, low wages, no rotation of work and discrimination against, those who rebelled and/or were known union members. Our Guys began to boil over.

Risking their livelihoods and their physical safety they began to organize. They got back into the ILA. The ILA, the Pacific Coast District, began to stir; geared up for a fight.. For the first time the Waterfront Employers faced longshoremen who, learning their lesson from the employers, were united on a coastwise basis. The demands were basic: A Coastwise contract.

Control of the hiring halls. No more piecemeal negotiating. No more playing one local in one port against another local in another port. Fair rotary hiring with no more shape-ups and no more payoffs to the Man. Men Who had been hammered and beaten and degraded, who had become isolated socially from "uptown people" and from that isolation had become united as longshoremen and proud of being longshoremen, stood solidly up and down the coast and went for broke.

They went on strike. In Seattle, Our Guys put 1400 men on tile picket line the very first day. The story of the 1934 strike and Bloody Thursday are well known. Not only did it mark a turning point in the history of maritime trade unionism, it marked a turning point in the history of the American trade union movement. It struck a spark that spread throughout the country. Every trick in the book, every kind of available force was thrown at Our Guys. The battle was bloody and long. But they won.

Unity. that did the trick. The coming of the ILWU in 1937 cemented that unity, gave it a guarantee of rank and file control. Every time you go to your union hall and get dispatched under rules you voted for by a Dispatcher you elected... Every time you go to a job with decent working conditions and wages...

Every time you or a member of your family gets good and free health and dental care... Every day you live under a Pension Plan that frees you from the fear of winding up on the junk heap old and sick and homeless and hungry... then you just thank those old Guys who gave us the Union that made all these things possible.

We owe it to them. Today we gather to thank them and honor them, those abused, shabby, maligned, shadowy and nameless Our Guys from those who met with Terry King in that shack June 12 1886, to all those Guys on down the line who got. knocked down and kept getting up for more and never let the fire go out.

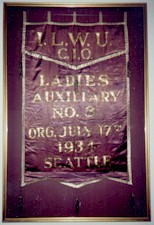

The

Federated Auxiliary ILWU This arm of the ILWU was literally born under

fire smoke-bombs vomit-bombs, bats, rocks and clubs, mounted police,

armed police.

The

Federated Auxiliary ILWU This arm of the ILWU was literally born under

fire smoke-bombs vomit-bombs, bats, rocks and clubs, mounted police,

armed police.

The Longshore wives took care of the wounded and bloodied men who gathered at the union hall. they cooked food, made coffee, kept up the soup kitchen for their men on the picket lines of 1934.

Over the years, it has developed into a strong-minded, community organization of women who keep up with local and national affairs, write letters on legislative issues, send delegations to their congressmen, use political activity, give scholarships to ILWU children, assist when called upon for help from other unions, and who have walked a few picket lines themselves.

The auxiliary is a going concern industrious and sharp, holding a Biennial Convention of their own, coastwise. Proud of the ILWU, and Local 19 is proud of them -- Auxiliary #3, Seattle. Trade Union Cooperation.

The ILWU was largely responsible for two epic periods of cooperation among trade unions for the benefit of all, which are noteworthy for their existence alone, and for the enthusiasm they created and the great gains brought to all unions who worked together within the organizations. THE MARITIME FEDERATION OF THE PACIFIC, organized in 1935, published a in militant newspaper, distributed up and down the coast, and the longshoremen surged ahead to win load limits, eliminated speed-up which pitted each gang against the other, and thereby also influenced the work within the gang just as piece work does.

The strongest work themselves to death to keep ahead, the weaker can't keep up and are fired. The right to refuse to work when health or safety was concerned made its bow in 1940; and in 1941, a list of noxious, dangerous cargoes was gained coastwise, which would pay penalty time if worked.

In 1944 penalty rates and skill differentials paid time and a half for overtime for the first. time. The FEDERATION did its work well, but was scuttled by Lundeberg of the SUP. In 1946 the COMMITTEE FOR MARITIME UNITY sprang up

Because of the need for cooperation among the unions to make worthwhile gains. Six unions banded together, met together, negotiated together, fought together, and came out without a strike, and with gains for all.

For longshoremen, vacations,

Saturday as an overtime day, Sunday 4 hour call-in pay and holidays full

pay for stand by time. A no discrimination clause was written into the

contract, and a long needed Safety Code was also included. Curran of NMU

managed to deep six this committee.

While ILWU Was

Flourishing

While the union was chalking up a

victory against the old shape-up, kick back hiring procedures and

establishing a rotary dispatching and hiring hall for longshoremen on

the west coast, gaining pensions and medical coverage not only for

themselves but, for their families.

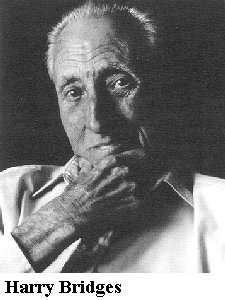

Plus a working safety code which saved life and limb, and helped longshoremen gain better wages and working conditions, Harry Bridges himself was undergoing a personal attack which lasted over 25 years. Unprecedented and disgraceful.

Of course the attack was actually on the ILWU; and the rank and file was well aware of this displayed great courage and fortitude in giving support in every way.

Besides investigations in 1934 and 1935 by the Immigration and Naturalization Department (which finally concluded that such investigations failed to show that he (Bridges) is in any manner connected with the Communist Party or with any radical organization)1936 brought the first of five long and arduous, costly trials, lasting through 1956.

All again and again, displayed the paucity of evidence against Bridges through the trail of paid witnesses, liars disgruntled ex-union officials, ex-convicts, finks and goons which paraded through the five trials.

Bridges was under constant surveillance by private detectives, police. tapped phones, bugged rooms, stolen papers all the time. One Supreme Court Justice (Murphy) wrote at the time of his first vindication, "The record in this case will stand forever as a monument to mans intolerance of man.

Finally, Bridges was allowed to file for citizenship, June 23, 1945: took the oath of a citizen September 17. May 1949 Bridges, Robertson and Schmidt were indicted for criminal fraud and conspiracy. (based on Bridges' answer to the usual question of membership in the Communist Party "I have not, I do not:')

Found guilty in April, 1950 the three were sentenced along with their attorneys to prison, released on bail pending appeal. July 31,1950 bail was revoked, and Bridges went to prison for 21 days for saying at a union meeting of his own Local 10 that the local should go on record for an immediate cease-fire in Korea, with the issues going to the UN for settlement.

Bridges was vindicated in all

cases but the cost was high,-- time wasted which could be spent working

for further improvements for the ILWU Such was the strength and

integrity of this leader of he ILWU that he is known throughout the

world of working men and women, honored and revered to this day.

Welfare and

Pensions Negotiated

In 1949 ILWU negotiated with the P M A for a Welfare Plan for dock

workers and families which went into action in 1950.

At that time the employers were putting into the fund 3 cents per man hour a benefit which has been a saving grace for longshoremen, as all workers fear accidents, unexpected illness in the family and huge hospital bills.

The Fund has grown to include; dentistry, eye car, prescription drugs, and other benefits. July 1952 saw longshoremen up and down the coast hanging the hook and retiring with, a pension of $100 a month plus social security, medical care for life, and life insurance.

Whether they finally got the "Chicken Ranch" they had talked about for years, or whether they just returned to the pensioner's hall in the Longshore building to keep "working cargo" with the rest of the old timers, or playing tonk, talking about old times --- they went out in style! I hey deserved it.

Their militant record of unionism paid off not only for themselves but for the young men and women who are slowly working their own way toward retirement, enjoying good wages, overtime, scheduled days off, vacations. Cradle to the Grave Security.

The Shape-Up -Vignette

Joe Dougherty pulled his coat tighter against the

chill morning air. His ears burned from the icy wind that swirled across

Elliott Bay. Blowing into cupped hands to relieve the painful

numbness in his fingers he peered anxiously through the locked gate at

the head of Pier 2. Beyond it, just visible in the darkness rose the

hull of a large cargo ship.

He reached into his pocket for a lucky and then turned to his partner. "You'd think some of these guys would stay home on a day like this, wouldn't you Snapper?" He waved one arm at the crowd gathering in the street around them and searched for a match with the other.

"There's at least. a hundred of and more coming," he added, looking over his shoulder. "Not even a fleet of ships could put everybody here to work!" Snapper found a book of matches in his overalls and reached up to light Joe's cigarette." Why don't we try Smith Cove instead?" he suggested, examining the crowd for the first time.

Some of the men, like himself were dockworkers by trade. But most were younger war veterans and unemployeds. Many had arrived hours earlier to get a place at the head of the throng. "Smith's a long way to walk? Joe shook his Head. "Shape-up might be over by the time we got there. Aren't there any ships closer' in?" "We could hop a streetcar. There's bound to be less guys out there." 'I dunno."

Joe glanced towards the dock apron. "There's four hatches on that boat--they'll need at least eighty men? Joe and Snapper weren't the only ones discussing their chances of being hired. Clusters of men huddled over newspapers, scanning the trade section with keen interest for new ship arrivals.

The sound of sleet as it began to hit the pavement drowned their voices and the dampened crowd moved closer together as they waited for the hiring boss to appear Joe recognized a couple of regulars from one of the Pier 2 company gangs as they filed past him towards the front of the crowd.

They would be hired before anyone else. "C'mon Snapper, let's go. We don't have a chance here' "Whaddya mean? You were just saying how big that ship was "Yeah. But with the company gangs and this crowd we might as well be two pennies in a slot machine." "Damn it ---why don't we get into one of those company gangs?

We'd never have to worry about getting hired' "The day I have to sell my soul for the privilege of working is the day I retire!" Just then the hiring boss, an ex-seaman by the name of Skiff Hanson stepped from behind the warehouse door and conversation ceased.

He had an easy, confident step as he started towards the pier gate. His thumbs were shoved in to the thick leather belt that strained to keep his formidable paunch in place. Two large brushes of yellow whiskers spread out from beneath his nose like the handlebars of a bicycle and a faint orange glow marked the butt of his stogie between them.

Some of the regulars had watched Hanson make his walk across the pier every morning for years. Still they waited nervously. Would he remember their loyalty to the company? Or would he give some newcomer the job today? They studied his gait as if to glean the answer. "All right boys, shape up!'' As the gate swung wide the men shuffled into a horseshoe around Hanson.

I his small gray eves slowly surveyed the men in front "Damn!" Joe swore under his breath . "We shoulda gone to Smith? "Why?" Joe nodded to a knot of men in front. All had just placed tooth picks in the corners of their mouths "Why d'ya think they're all standing together" Joe demanded." They all went to the same restaurant for breakfast?'' ''Don't, clown me, Snapper.

I smell a payoff." Sure enough, Hanson pointed to the men with toothpicks." You there --- Number One hatch: deck, dock and hold!" "Hey Skiff, what gives? Were the Number One gang." It was one of the regulars. Hanson's eyes fastened on him and then narrowed to line slits." What did you say, Jackson? his voice was menacing.

The man looked from side to side. But his partners stared straight ahead as if they didn't know him. Jackson's anger turned to confusion and finally silence before Hanson's glare." Don't ever come here looking for work again, Jackson."

Without a pause, Hanson resumed dispatch. Calling out the company gangs first, he then filled in with extra men. When all of the jobs were assigned roughly half the crowd still remained. "That's it boys! But stick around. There's another ship due in late tonight." "What does Hanson think we are, stooges? There's no ship in here tonight Snapper muttered..

"He just wants to be sure somebody's here when they start dropping like flies" Joe snorted. "His gang bosses don't give breaks. Come on, let's beat it over to Smith." "Right," Snapper agreed as the crowd hurriedly disbanded ''Before everybody else does!" This material was put together by the ILWU Centennial Committee 1986

This material was prepared by the ILWU Centennial Committee 1986